Trump’s ‘America First’ Offensive: Meanings and Consequences

BGA Senior Adviser Thitinan Pongsudhirak wrote an update on the U.S. administration’s “America First” strategy.

President Donald Trump’s extraterritorial capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro on cocaine-trafficking and terrorism-related charges and renewed demands to take over Greenland for security reasons are part and parcel of a transformative “America First” paradigm that dates back at least four decades (see BGA’s update, “Trump II: Understanding Policy Prospects Under the Next US President”). This “America First” agenda has now culminated with and been codified into the U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS), launched in November 2025.

It behooves those who want to understand what Trump is doing and where he is going to take the NSS literally, putting aside his blustery self-absorption and vulgarity while focusing on the nativist and nationalistic movement behind him. Figuring out Trump’s mindset and maneuvers requires analyzing underpinnings, drivers and trends the way they are, rather than the way we want them to be.

To be sure, Trump’s first term pales in comparison with what he is doing now. On a visit to Southeast Asia for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations-related summits in November 2017, he set the tone in Asian geopolitics by proclaiming an era of “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” reinforced by the NSS 2017. This prioritized homeland security and prosperity and rebalanced hard interests over traditionally universalist values of rights and freedoms, while singling out China and Russia as revisionist powers. That Trump lost the next presidential term became a blessing in disguise for him as he spent the interim four years canvassing the grassroots in rural constituencies and building up his “Make America Great Again” base.

The presidential hiatus also enabled Trump, who had been more accustomed to the inner workings of New York’s Manhattan and Florida’s oceanside resorts, to set up his own shop inside the Washington beltway. He was then able to put together teams of like-minded anti-immigration nativists and pro-protectionism nationalists, while consolidating the party he wrested away from traditional Republicans.

Trump appears to be working both around and against the clock to indelibly implant his America First programs beyond reversibility. From the outset of his second term in early 2025, he wasted no time implementing policies and executive orders big and small, including a symbolic name change to the Gulf of America in place of the Gulf of Mexico. Trump’s nativist camp erected barriers to keep out near-abroad migrants and secured borders in a fortress-like fashion. By April 2, the so-called “liberation day,” Trump unilaterally imposed tariffs on all other economies, including staunch allies like Canada, the United Kingdom and Japan.

His weaponization of the U.S. market as the world’s top export destination undermined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and virtually upended the multilateral trading system. Not a day goes by without Trump spouting words and taking actions that quicken the breakdown of the international system as we know it. The Maduro gambit and the Greenland takeover threat will likely be followed by a continuous slew of belligerent moves to reshape the home front and remake the international system to Washington’s advantage at the expense of global peace and stability.

For many, it is difficult to come to grips with all that Trump is doing because we have been the beneficiaries of the 80-year-old international system which he is blatantly and systematically dismantling. Unsurprisingly, there is — and will be — a lot of kicking and screaming, lamenting and yearning along the way as the current global system is uprooted during the remainder of Trump’s second term.

But the sooner we get our heads around it, the better we will be able to adjust. Besides, the international system had been coming loose at the seams well before Trump entered the fray. From 2001, the WTO’s Doha Round of trade liberalization became bogged down and eventually moribund. The harbinger of its demise can be traced to the acrimonious and delayed conclusion of the preceding Uruguay Round in the early 1990s. Bilateral and regional trade arrangements have superseded multilateral negotiations since.

The international financial system had been convulsed by periodic crises that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was hard pressed to preempt and could only bail out with controversial orthodox, austere recipes that further caused resentment and grievances among developing economies. Moreover, that the World Bank’s head had to be American and the IMF’s counterpart had to be French all this time was not well received by rule-takers of the international system. The United Nations became similarly outdated as decades went by and its founding charter was violated time and again, exacerbated by the veto privileges of its five permanent members, including the United Kingdom and France, which can no longer claim much economic share and geopolitical weight compared to the rest of the world.

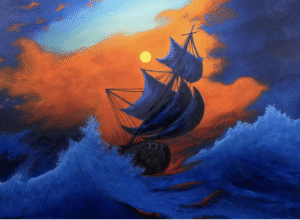

The international system had pretty much run its course by the time Trump and his movement came along. He is less the cause and more the catalyst of its unraveling, now accelerated by his American First mantra and manifestations. As the international system falls apart and new global arrangements take time to settle and solidify, the interregnum will induce seeming chaos and confusion. Much will depend on how the America First manifesto in the NSS 2025 unfolds.

It is a document that upgrades the Monroe Doctrine — the so-called “Donroe Doctrine” by media coinage — to include the “Trump corollary” of exclusive U.S. supremacy in the Western Hemisphere, which henceforth becomes off limits to China and Russia as opposed to European colonial powers two centuries ago. This bold geostrategic declaration is going to keep the United States preoccupied and busy in its neighborhood and near-abroad. From Venezuela and Greenland to the rest of the American continental landmass and proximate islands between the Atlantic and Pacific, the United States is now supposed to be the dominant epicenter.

The flipside of this hemispheric dominance is the prevention of others, namely China and Russia, from access and competition. We can call this strategy “anti-access/hemisphere denial,” a U.S.-owned version of anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) pursued in Asia and elsewhere. The idea is to deny access of the Western Hemisphere to adversaries and to complicate and constrain their presence, role and maneuverability if they somehow get there. The Trump team’s hemispheric geostrategy will bear implications and consequences far and wide in the foreseeable horizon.

For now, economies and firms everywhere should accept the cold reality that the international system is unraveling, that America First is a real deal not to be underestimated or ridiculed, and that more geostrategic turbulence is in store. It is early days to anticipate how firms should adjust their strategies, but perhaps it is time to start thinking “hemispherically” with an awareness for crisscrossing bilateral and regional free trade agreements and an eye on Indo-Pacific growth areas that the NSS 2025 acknowledges.

If you have comments or questions, please contact BGA Senior Adviser Thitinan Pongsudhirak at thitinan@bowergroupasia.com.

Best regards,

BowerGroupAsia

Dr. Thitinan Pongsudhirak

Senior Advisor